Truthfully, scholarship, research, and creative activity are complicated, layered, multi-faceted, crazy-awesome ways for us to grow, learn, appreciate, share, wonder, teach, and discover.

This page will introduce you to some ways to think about research - there are many more. Part of the journey is to figure out what is best for you, your community, and the project. VIU has lots of wonderful resources to help you along your way. Welcome to the wonderful worlds of research!

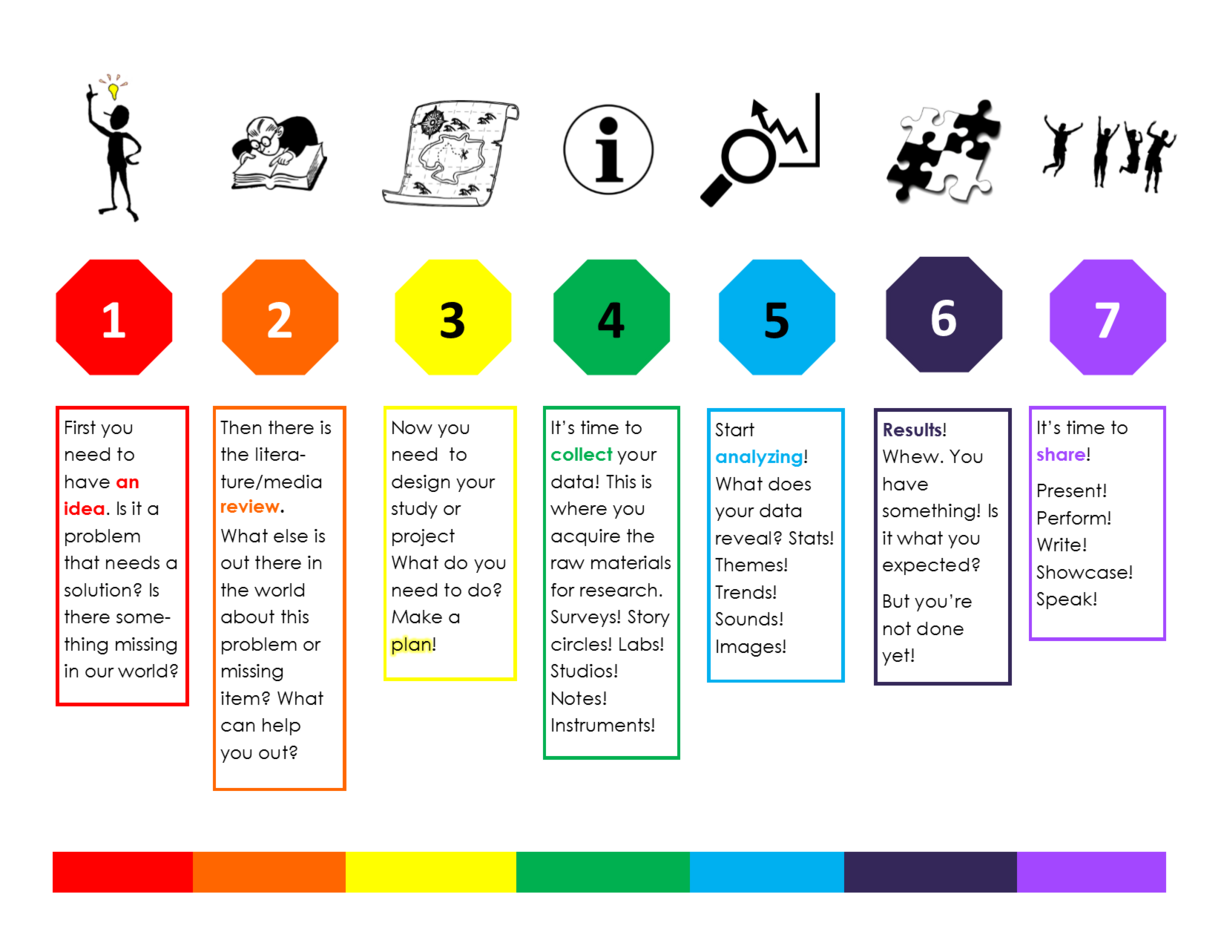

This is a general linear way to think about things, but it doesn't work all the time. It may need to shift, change, or be completely dismantled in order to allow the project to find its best voice.

Now remember - this is just the basics! If you are interested in the specifics of particular types of research - great! There are a number of courses, books, web resources at your disposal.

What is Qualitative Research?

Quantitative research is the process of collecting and analyzing numerical data. If can be used to find patterns and averages, make predications, test causal relationships, and generalize results to wider populations (Bhandari, 2021).

What is Qualitative Research?

Qualitative research involves collecting and analyzing non-numerical data (e.g., text, video, or audio) to understand concepts, opinions, or experiences. It can be used to gather in-depth insights into a problem or generate new ideas for research (Bhandari, 2020).

What is 'mixed'?

Mixed methods is basically a research approach that collects and analyses both quantitative and qualitative data within the same study.

For example, say I asked 5 people if they preferred qualitative or quantitative research. All five replied with quantitative (a quantitative data set). Then I asked those 5 people why they preferred quantitative. All of a sudden this inquiry requires a qualitative lens as it wound be difficult to answer 'why' with just numbers.

Quick Reference Chart - not the be all end all!

| Characteristic | Quantitative | Qualitative |

|---|---|---|

| Origins | Natural Science | Social Science |

| Philosophic Roots | Positivism Empiricism | Naruralism Phenomenology |

| Research design | Deductive | Inductive |

| Data | Numeric | Non-numeric |

Data collection examples | Instrument outputs Surveys | Interviews Focus groups |

| Analysis | Statistical | Non-statistical |

| Goal of investigation | Prediction, control, confirmation, hypothesis testing | Understanding, description, discovery, hypothesis generating |

Chart adapted by author from Merriam, 1989; Pierce, 2008; Yin, 1995

* This is a fantastic summary from Len Pierre who is currently the Special Advisor, Indigenous Leadership, Innovation, and Partnerships at Kwantlen Polytechnic University. Sourced from Two-Eye Seeing in Research.

A - Acknowledge your point of departure. What are the laws, customs, traditions, values, beliefs, and people of the land?

B - Build relationships with Indigenous stakeholders that is founded on proactivity, equality, and reciprocity.

C - Cultural Humility. I know some things but I don't know everything. My reality is not necessarily other peoples reality.

D - Decision-making style. Who is involved? Who has autonomy? Who is missing from this phase/stage in the project?

E - Embed Indigenous knowledge and values into the fabric of your project, not just as an add on.

F - Follow before you lead

G - Ground the work in resilience and strengths-based

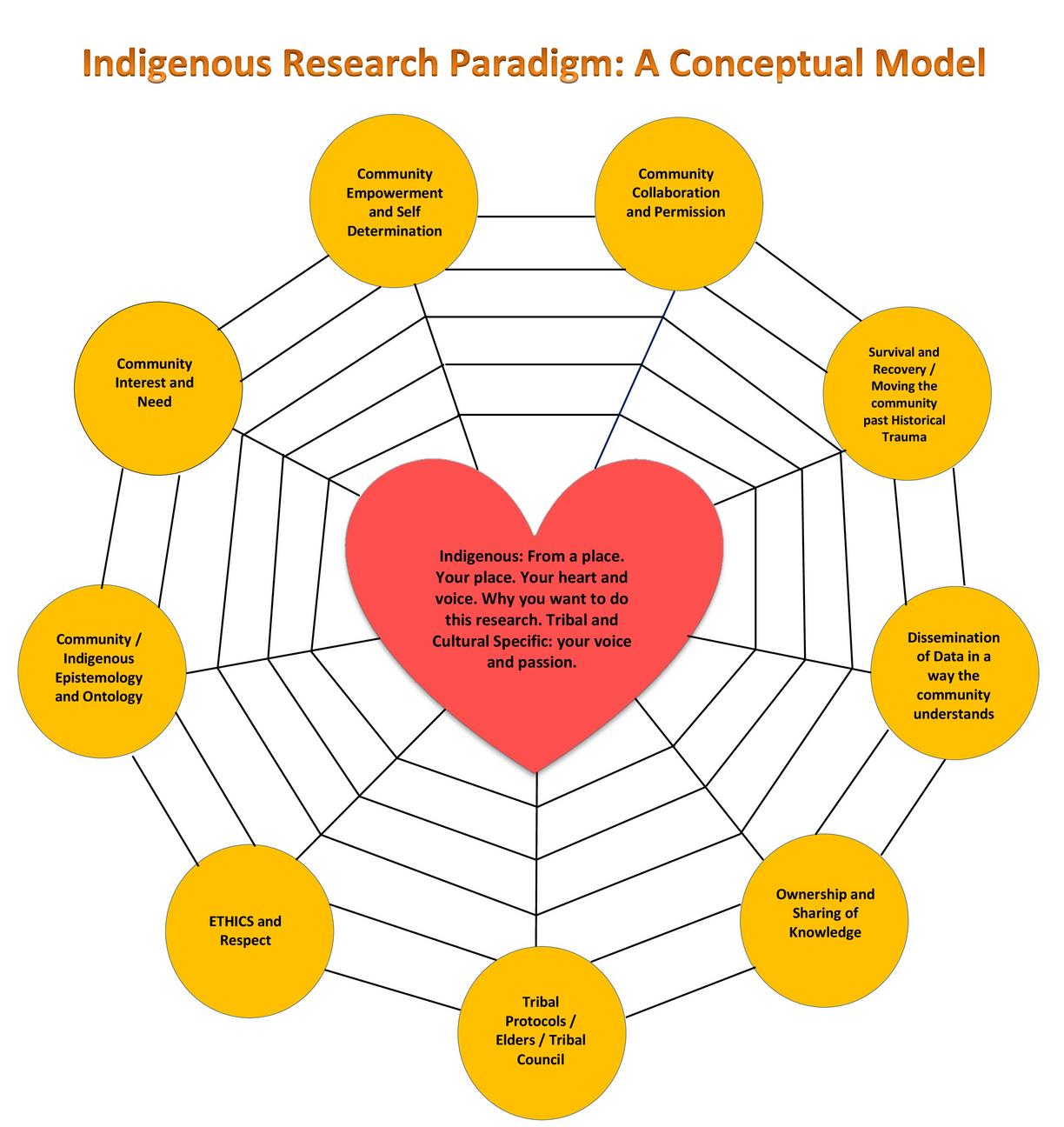

H - Honour Indigenous research methodologies: talking circles, artwork, story work, ceremony, Elders, Knowledge Keepers, Land as Literacy, Cultural Protocols.

Mi’kmaw Elder Albert Marshall defines Two-Eyed Seeing (Etuaptmumk in Mi'kmaw) as “learning to see from one eye with the strengths of Indigenous knowledges and ways of knowing, and from the other eye with the strengths of mainstream knowledges and ways of knowing, and to use both these eyes together, for the benefit of all” (Bartlett et al., 2012).

(Thanks to Sandra Mathison, a prof at UBC, for her excellent blog Qualitative Research Cafe for this succinct reflection on Anti-racist methodologies. This section is taken from her blog with permission.)

Anti-racist research is generally situated within a critical research theoretical perspective given the focus on differential access to power for minoritized people seen through the lens of race, class, gender, and sexuality. Anti-racist research is not content with describing and understanding differences, but intends to understand, challenge and change values, beliefs and actions that sustain systemic racism.

Anti-racist research methodologies include critical ethnography, critical discourse analysis, critical narrative inquiry, and Indigenous research methodologies with attention to the relational aspects of research, that is, doing research with, not on, BIPOC.