The Vancouver Island University community acknowledges and thanks the Qualicum, K’ómoks, Snuneymuxw, Quw’utsun, Tla’amin, and Snaw-naw-as on whose traditional lands we teach, learn, research, live and share knowledge.

"In our history, we have always been here. Our old people say there were village sites below the low water marks and on the mountains. I think it speaks to how long we have been here - in our story we have always been here. "

Carrie Reid, Qualicum First Nation Member

The following information is a collection of information, largely an oral history as told by Qualicum First Nation member, Carrie Reid, during an interview with Deep Bay Marine Field Station staff on February 3, 2021. Additional information added is noted with references at the bottom of the page.

Deep cultural connection with marine resources

The name Qualicum itself comes from the name for 'dog salmon', or chum salmon, as places were previously named not after people but after the qualities of the land. The Qualicum region was a gathering place where people from all over would come to harvest camas flowers in the spring and then catch chum salmon in the fall. They would smoke their fish in the smokehouses and then head home.

"Everything was centered around the ocean."

The ocean acted as a 'traditional highway', as people could paddle from Bella Coola to Victoria in two days if they caught the right current and tides. The knowledge of the ocean, tides and currents were an integral part of not only transportation, but for collecting food as well.

A significant part of the traditional diet are clams, including geoducks, horse clams and butter clams.

"I can remember my Grandpa going down the beach and he would just pick up a horse clam and bite its nose off."

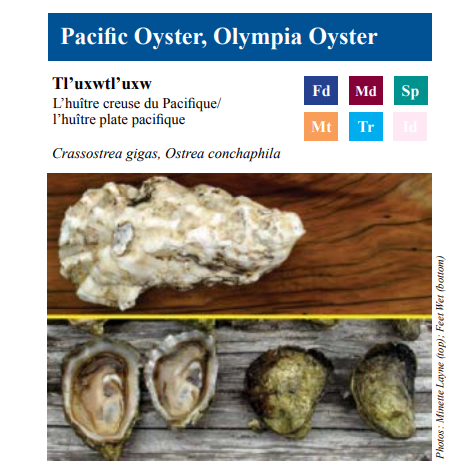

Abalone were also consumed, often dived for in the Deep Bay area. Olympia oysters, the native oyster, have also been found in large middens along coastal BC, some of which have dated back 10,000 years (1). Previous research has suggested that the Olympia oysters were not typically harvested for consumption, but rather as bait for herring fishing (2). The tradition of using prey as bait continued, as herring caught was then used as bait for salmon (3). Research suggests and oral history confirms that the Deep Bay area saw an increase in population seasonally, typically spring, to collect the herring as well as dig for clams and hunt for male deer (3).

A silent language

Puntledge, Pentlatch, or Puntlatch is the language that was spoken from around Comox to Parksville; and Port Alberni to the islands of Denman, Hornby, Lasquti and Texada. In 1942 the language was officially declared 'extinct' by the government when the remaining fluent speaker, Joe Nimnim, died (4); however, The Qualicum First Nation would like to recognize Juliana Jim, who also spoke Pentlatch until the 1960's.

Own work by Nikater, submitted to the public domain. Background map courtesy of Demis

Jessie Recalma of the Qualicum First Nation noted in a recent interview with the CBC that the reason for the loss of the Pentlatch language was largely due to loss of the population due to small pox, in addition to war and other languages moving in (5). There may also have been 'silent speakers' - those who had knowledge of the language but did not speak it for fear of punishment while in residential schools (6).

Cultural identity is linked to language, and to help preserve this part of their heritage, members of the Qualicum First Nation are working towards declaring Pentlatch the 35th official Indigenous language in BC (5).

“We are in the time of extinction for some words. Elephant Seal. I’ve been looking for two years to try to find a word for elephant seal. Because they were gone for so long, all of the people who knew the names are dead. I’ll take any Salish word for elephant seal.” -Carrie Reid

Boys sitting by marina in Deep Bay, date unknown, QFN Archives

From left: Gordon Reid, Ray Recalma, Unknown at this time, Dave Reid

Chrome Island - "Dog Island"

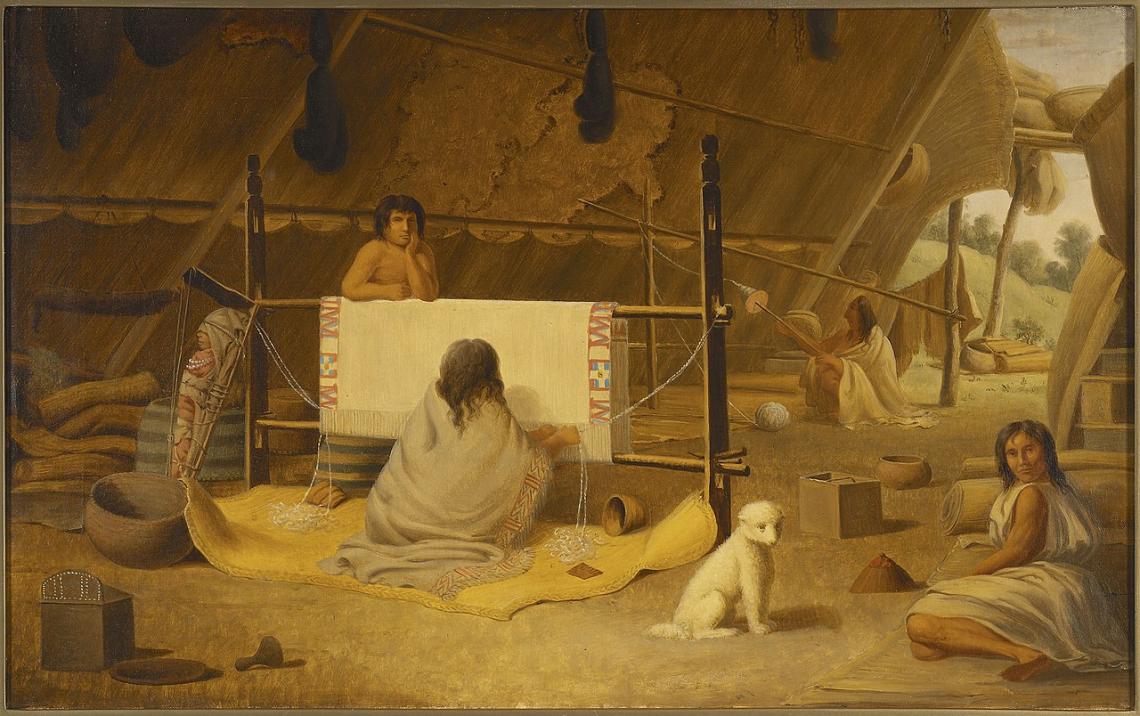

Part of the Qualicum First Nation's Traditional Land includes Chrome Island, which is between Vancouver Island and Denman Island. It was referred to as ch’namen or 'dog island' as there was a breed of dog that was kept on the island that they would sheer for wool. People used to show their wealth by giving blankets away, so they would raise several wool dogs on the island. The dogs were owned by the women.

Looking out to Chrome Island from Deep Bay Spit

Hunting dogs were also commonly used but the people did not want the hunting dogs and wool dogs to mix, so keeping the wool dogs on the island was the easiest way to ensure this. The women would go to the island a few times a week to feed the dogs, and once or twice a year to cut their wool using mussel-shelled knives (7).

This 'Salish woolly' breed was likely similar to akita, chowchow or husky breeds, with long and thick fur. Students have suggested remains of this breed have been dated back as far as 5000 years old on Vancouver Island (8).

Coast Salish weaver creating a blanket from dog wool, painting by Paul Kane 1840s

For more information about woolly dogs, and the women who cared for them, read this article on the subject from Hakai Magazine.

Next Steps for Deep Bay Marine Field Station

This website is part of an ongoing project. We at the Deep Bay Marine Field Station deeply thank Carrie Reid and the people of the Qualicum First Nation for their time, knowledge and support with this project.

Next steps include incorporating Salishan languages, such as Pentlatch, Hul’q’umi’num and Tla a'min, for places and names at the station. For Hul’q’umi’num names of local species, including marine animals, please refer to Ecosystem Guide - A Hul’q’umi’num’ language guide to plants and animals of southern Vancouver Island, the Gulf Islands and the Salish Sea.

Excerpt from "Ecosystem Guide - A Hul’q’umi’num’ language guide to plants and animals of southern Vancouver Island, the Gulf Islands and the Salish Sea". Page 98. A publication of the Hul’qumi’num Treaty Group

References

1. Ucluelet Aquarium. (2021). Small yet mighty: The rise of Olympia oysters. Retrieved from https://uclueletaquarium.org/small-yet-mighty-rise-olympia-oysters/

2. Burchell, Meghan, The mid-holocene landscape of Deep Bay: a multi-proxy approach to palaeoenvironmental reconstruction from shell midden deposits in coastal British Columbia, Canada (invited presentation). GSA Annual Meeting in Indianapolis, Indiana, USA - 2018. 10.1130/abs/2018AM-318871. Retrieved from: file:///C:/Users/armeta/Downloads/AbstractGSA2018.pdf

3. Monks, Gregory G. “Prey as Bait: The Deep Bay Example.” Canadian Journal of Archaeology / Journal Canadien d’Archéologie, vol. 11, 1987, pp. 119–42. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41102383. Accessed 29 Sep. 2022.

4. Qualicum Beach Museum. (2022). Our language is our cultural and social identity, We are claiming it back [Museum Label]. Qualicum Beach, B.C.: Author Unknown.

5. CBC. (2022). Revitalizing Indigenous languages: Meet some of the people working to keep their language alive. Retrieved from https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/revitaliizing-indigenous...

6. CBC. (2021). Revitalizing Vancouver Island’s Indigenous languages. Retrieved from https://newsinteractives.cbc.ca/indigenous-languages-vancouver-island/

7. Hakai Magazine. (2021). The Dogs That Grew Wool and the People Who Love Them. Retrieved from: https://hakaimagazine.com/features/the-dogs-that-grew-wool-and-the-peopl...

8. Times Colonist. (2020). Woolly dog valued for its hair, lived on marine fish, researchers find. Retrieved from: https://www.timescolonist.com/local-news/woolly-dog-valued-for-its-hair-...