An Almost Forgotten History of Native Oysters on Vancouver Island

We have been searching through 1800’s literature and newspapers to track the exploitation and disappearance of Native (Olympia) oysters from Baynes Sound and Vancouver Island as a whole. This is our longest post to date but is some research we are very excited about. We hope you enjoy this almost forgotten chapter of Vancouver Island estuarine ecosystems. This has been a join effort of Brian Kingzett and Karen Leask (VIU) and Melissa Frey of the Royal BC Museum with supportive comments and help from many.Last year we worked again with funding from Environment Canada Habitat Stewardship Fund to initiate Native Olympia oyster restoration activities in Baynes Sound.

See Previous blog articles on our Native oyster work:

The Native or Olympia oyster (Ostrea lurida) is an integral part of the Pacific Northwest as are Pacific salmon, yet because of its near annihilation a century ago, it has mostly slipped beneath the threshold of public awareness. Olympia oysters are BC’s only native oyster and were listed under SARA as a species of special concern in 2003 and are Blue listed by the Province of British Columbia (BC). Until the late 1800s, Olympia oysters were highly abundant, supporting sustenance and commercial fisheries and occupying thousands of acres of productive, diverse habitat. But much of the recorded history of the Olympia oyster is for the US or in the early 20th century and very little exists for British Columbia.

Beginning with the California gold rush and then extending north up the coast; over-exploitation, habitat alteration and pollution led to significant declines in Olympia oyster beds throughout their range along the Pacific coast of North America and near-extirpation in some areas. While remnant populations can still be found today, this species occupies a fraction of its former range in vastly lower numbers and is now functionally extinct through many of the estuaries where it once thrived.

Since the early 1900s, impacts on the Olympia oyster have been dramatically reduced with the collapse and closure of the fisheries and reductions in pollution and habitat alteration, such as improved industrial practices to reduce sedimentation rates in estuaries. Despite this, their populations have not rebounded. This has led to impressive restoration efforts in the United States; despite a serious lack of basic research and knowledge on the species. Restoration efforts are driven by several motivations including the desire to restore important ecosystem services provided by healthy estuaries (e.g. water filtration, shoreline stabilization and creation of important biogenic structure), a desire to restore a native species at risk of extirpation, and the potential of farming a native species of oyster for commercial harvest.

In 2008, the CSR starting working with the Puget Sound Restoration Fund led by our great friend Betsy Peabody, and the Nature Conservancy to look for the last “ecologically functional” populations of this species in Nootka Sound. Joined by Fisheries and Oceans Canada staff and aided by local oyster farmer Bob Devault we have made three trips to Nootka Sound to study what maybe some of the last intact reefs. What we found on those trips was pretty amazing; intact reefs of this species, unlike anything any of our “Olympia oyster experts” had ever seen. These are believed to the last few acres of intact reefs – the mountain gorilla of oysters as it were. This work was described by authour and oyster aficionado Rowan Jacobsen in his book the “Living Shore“.

In the Strait of Georgia, our work has included summer students looking for trends in larval recruitment between Ladysmith Harbour and Union Bay, and at the Deep Bay Marine Field Station we have now conducted two summers of developing hatchery capacity and producing seed of Native Oysters with the goal of developing a broodstock pool within the Sound on our research farm. The use of increasing broodstock populations has been shown to be effective in Puget Sound when suitable habitat is available. We have received funding from the Environment Canada Habitat Stewardship Fund and the Canadian Wildlife Foundation. We have been working with biologists at Fisheries and Oceans Canada, the Puget Sound Restoration Fund, World Fisheries Trust and Melissa Frey, Invertebrate Curator at the Royal BC Museum. We’ve spent a lot of our own time on the project and even though there are a dedicated and interested group across a number of organizations the effort is extremely small in comparison to some of the US initiatives.

Our first version of our Native Oyster Hatchery

To us the habitat in Baynes Sound looks good, but no one we have ever met has ever recounted finding or knowing of Native oysters in the Sound in recent memory. To this end we have been (legitimately) asked if Native oysters have ever been in the Sound and if not, is it appropriate to be trying to restore them where they might not have been? Our own informal surveys of the sound have found Native oysters but very few and far between and when we do they are typically very cryptic, underneath rocks.

A single lonely Native Oyster found in Baynes Sound (attached to an old Pacific Oyster)

This started a hunt to see whether they had been here in the past. Coming across a reference to an “Oysterbed Rapids” in Victoria sent us on a search for an early map, sketched in 1846, on which this was the name given to the Gorge waterway at Tillicum Narrows[1]. That is surely a testament to the early abundance of Native oysters in the Victoria area.

Early biological work on this species by Fisheries scientists began with Stafford in 1911[2] and 1913[3],and Elsey in 1933[4]. After spending the summer of 1913 surveying the coast of BC from Victoria to Queen Charlotte Sound for Native oysters and their larvae, Stafford found many oysters on the west side of Campbell Island, Blunden Harbour, Nanoose Bay, and Oyster (Ladysmith) Harbour, and while he did recognized Native oyster larvae in samples from Comox Harbour and in Deep Bay he found only a few oysters on the beach at Comox. Elsey mentions Boundary Bay, Portage Inlet, Ladysmith Harbour and Nanoose Bay but does not discuss Baynes Sound at all. A more recent attempt by Fisheries and Ocean’s biologists[5] to confirm some of the historical reports of large quantities of Native oysters, found high abundance on a few beaches on the west coast of Vancouver Island, some Central coast mainland bays and inlets, as well as Ladysmith Harbour and the Gorge Waterway in Victoria, but only scattered animals were found at most other sites along the east coast of Vancouver Island and at Boundary Bay where they were actively cultured through the 1930s. This recent report of only a few oysters on several beaches in Baynes Sound, from Comox Harbour to Fanny Bay, is reminiscent of Stafford’s account of 1913. Based on the scientific history it did not look too promising.

Melissa Frey made the point that the archives of the British Colonist (also called the Victoria Daily Colonist) newspaper are now online, searchable and housed by the University of Victoria (British Colonist), and that she had found an article about Native women selling oysters in the 1860’s. The British Colonist archives are a fantastic resource about the history and culture of Vancouver Island since 1858.

This started a hunt to see whether we could trace the history of oysters on Vancouver Island and find out whether native oysters were ever recorded from Baynes Sound. We found much more than we expected, in fact a fantastic history of the exploitation and consumption of oysters on Vancouver Island. Admittedly much of this has meant some “reading between the lines” but from this archive we have been able to infer much about what happened before the scientists showed up. Quite a few evenings have now been lost to paging through the back issues of the paper.

Two of Victoria’s founding newspapers, the Victoria Gazette (also online and searchable through the University of Victoria[6]) and the British Colonist, had been in publication for less than a year when the first newspaper record of an oyster bar, Rudolph’s Oyster Saloon in Victoria, shows up in 1859. To put it in context, Victoria as a city was only a few years old. In fact Victoria would not be officially a city for 3 more years. The Hudson’s Bay Company had opened a trading fort in 1843 but when gold was discovered in the Fraser Canyon in 1855, the population jumped from approximately 300 to more than 5000 in a few days. In 1859 Victoria was the port, supply base, and outfitting centre for miners on their way to the Caribou gold fields. It was also in 1859, that the Queen cancelled Hudson’s Bay Company’s Crown grant to the colony of Vancouver Island which meant losing its exclusive trading rights, and James Douglas became governor of the colony. The last palisades of the Fort were taken down and the first Parliament buildings, “The Birdcages”, were built on the south side of the Inner Harbour.

By 1861, the population of the colony of Vancouver Island through immigration was recorded in a dispatch from Governor Douglas to have reached 3024, of which 2350 were in the vicinity of Victoria[7]. The first government approved settlers of Comox didn’t arrive until the following year aboard the HMS Grappler[8].

Rudolphs Oyster Saloon: To the Public. Having lived in Victoria long enough to find that good malt liquor is a scarce article. I would respectfully call the attention of the public to the fact that the genuine stuff can be found at my saloon where also be found the News from all parts of the civilized world. Call and see me at Duffy’s old place on Waddington Street.

In 1861 – the first advertisement of oysters from Sooke, constantly on hand, appears for the Phoenix Saloon. The US Civil War is now underway and the Caribou Gold Rush begins. This is the first newspaper reference to where oysters are being harvested from.

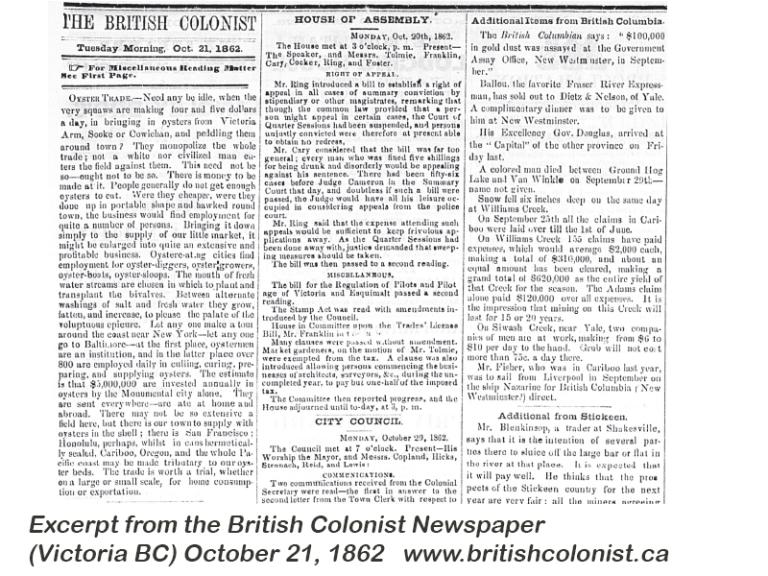

The first article about oysters in the Victoria Daily (British) Colonist appears in 1862. Assuming it was Amor de Cosmos the founder and editor who wrote the editorial, this starts the first of what will be particular interest in oysters by the newspaper. As an aside, the colorful Amore de Cosmos, who was born William Alexander Smith in Nova Scotia but changed his name in the California gold fields to reflect his “Love of order, beauty, the world and the universe”, seems like just the kind of guy to become a Vancouver Island Native and oyster lover. Amor de Cosmos would go on to be a Member of Parliament after Confederation and second Premier of BC, setting the stage for the wild ride of BC politics.

The first editorial is all about how Native women are dominating the trade in oysters. The commentary below must be read in light of the social conventions of the day.

October 21, 1862 British Colonist: “OYSTER TRADE –Need any be idle when the very squaws are making four and five dollars a day, in bringing in oysters from Victoria Arm, Sooke or Cowichan and peddling them around town? They monopolize the whole trade; not a white nor civilized man enters the field against them. This need not be so – ought not to be so. There is money to be made at it. People do not get enough oysters to eat. Were they cheaper, were they done up in a portable shape and hawked round town the business would find employment for quite a number of persons. Bringing it down simply to the supply of our little market, it might be enlarged into quite an extensive and profitable business. Oyster eating cities find employment for oyster diggers, oyster growers, oyster-boats, oyster-sloops. The mouths of fresh water streams are chosen in which to plant and transplant the bivalves. Between alternate washings and salt and freshwater they grow fatten and increase to please the palate of the voluptuous epicure. Let anyone make a tour around the coast near New York – let anyone go to Baltimore – at the first place, oystermen are an institution and in the latter place over 800 are employed daily in culling, curing, preparing and supplying oysters. The estimate is that $5,000,000 are invested annually in oysters by the Monumental city alone. They are sent everywhere – are at home and abroad. There may not be so extensive a field here but there is our town to supply with oysters in the shell; there is San Francisco; Honolulu, perhaps whilst in cans hermetically sealed, Cariboo, Oregon and the whole Pacific coast may be tributary to our oyster beds. The trade is worth a trail. Whether on a large or small scale, for home consumption of exportation. “

To put this in context $4-5 a day was also what a stone cutter and a blacksmith could earn and what house construction cost per day. In 1861, it cost $3 to shoe a horse, $2 for a pound of flour and $3 a pound for mutton, while a pound of coffee set one back $6[9].

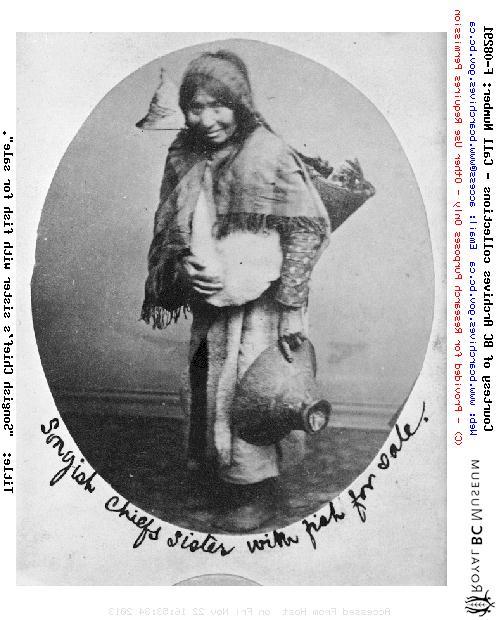

Songish (Songhees) Chief’s sister with Fish for sale – was this one of Victoria’s first oyster sellers? (Image F-08291 courtesy of Royal BC Museum, BC Archives)[10] The Caribou Gold Rush brought another flurry of economic activity to Victoria as another wave of miners began passing through the city in 1862, and Victoria was incorporated as a city. By 1865 – no less than four oyster bars are advertising in the Colonist, one with an external Oyster Stand – not bad for a community of just around 3000 people. In fact that is the same number of oyster bars in Victoria today!

Surprisingly oyster farming comes very quickly in the colony, a Mr. Busey is reported to have received permission to plant beds in Gorge Harbour to satisfy the “rage for oysters” (British Colonist 1865.09.26 P. 2). A similar experiment is being started in Esquimalt Harbour.

Less than a month later a Mr. Hughes is enthusiastically reported to be starting an extensive scale of farming in the well named Oyster Harbour, which we now know as Ladysmith (Times Colonist 1865.10.11 P. 2). At this time, the Cowichan Valley is a three day wagon ride around what will be the Malahat or accessible only by sail or canoe, but that was soon to change with the advent of the Victoria steam fleet.

The Editor of the day (Amor de Cosmos now gone on to the beginnings of a political career) remarks on Victoria’s total dependence on Olympia Oysters with farming operations now underway in Puget Sound. He also suggests that the colony is importing $500-700 a month of oysters during the winter. Some in the BC shellfish industry would argue that we are still working toward the eventual spoke in the wheel of progress mentioned……..

Additional Side note – the term “Siwash” was a then Chinook Jargon (trading language) word for a native person. Over time, the term (from the French “sauvage”, meaning wild or savage) developed an overtly offensive connotation that it still holds today.

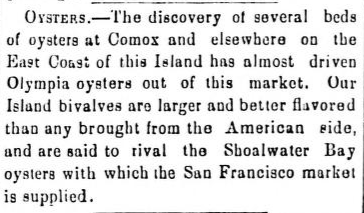

And then in the spring of 1866, Brian found the reference to the Oysters of Baynes Sound that no one believes existed. Oysters Discovered in Comox! (British Colonist 1866.04.02)

(Times Colonist, 1866.04.02 p. 3)

To give some background: The agricultural settlement at Comox, together with another at Cowichan, was founded in 1862 by the colonial government of Vancouver Island in order to expand European settlement of the island, which then extended little beyond the Victoria area and the small coal mining village of Nanaimo, and to provide livelihood for unemployed miners in the aftermath of the Cariboo gold rush.

The Mr. Hart, who is referenced in the following article, must most certainly be the John Hart who with his partner Captain Moses Philips (of the liquor smuggling schooner Explorer), established the first store in Comox and became the source of many problems for trading liquor to Natives prompting naval investigations and actions. In November of 1865, his establishment was described as “productive of great evil” among settlers. The Comox settlement was not a dull place as judged by the great (comic) potato war in November of 1965 when three Royal Navy gunships (including the Sutlej with >500 crew and > 30 heavy guns) had been dispatched over concerns that Cape Mudge (Euclataw) Natives had come down to steal the settlers potatoes as opposed to fish and work as labourers in the potato fields (seriously, read the great history linked above).

In 1866, John Hart had already been jailed and released early for landing liquor within a prohibited distance from a reserve. His presence in Victoria with twenty sacks of oysters establishes that from its earliest beginnings the shellfish industry was composed of “colourful?” characters. The steamship CGS Sir James Douglas noted in the above article was launched in 1865 for the Government service as the first lighthouse and buoy tender on the Pacific Coast. For over a quarter of a century, she was also an important line of communication along the east coast of Vancouver Island as she carried out postal service between Victoria, Nanaimo and Comox, as well as many other jobs like carrying settlers into the new areas of the province and transporting their products to market, like the potatoes and oysters mentioned in the article above. On more than one occasion she was also dispatched to collect survivors of shipwrecks along the coast.

CGS Sir James Douglas (Image C-03683 courtesy of Royal BC Museum, BC Archives )[11]

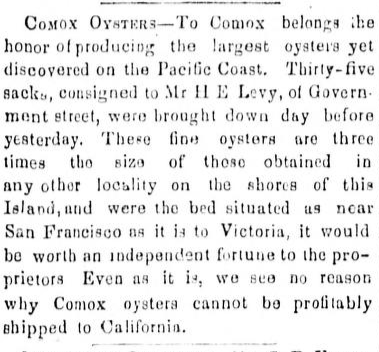

Interestingly, the same edition of the paper reports $90 of oysters exported to American Ports during month of March 1866, suggesting that local harvests were increasing enough to push back against the imports of Olympia Oysters. By September this new bounty of oysters from Baynes Sound seems to be doing just that (1866.09.27).

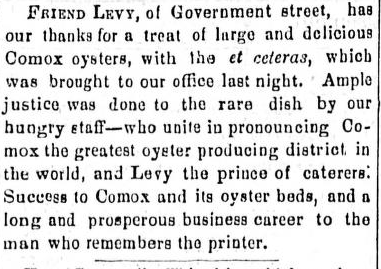

These oysters seem to be highly regarded as evidence by the following article from January 18, 1867 (P. 2). However a second article from the same edition (second below) suggests the amusing evidence of possible overt media manipulations.

“Comox the greatest producing district in the world and Levy the Prince of Caterers. Success to Comox and its oyster beds and long and prosperous business career to the man who remembers the printer!”

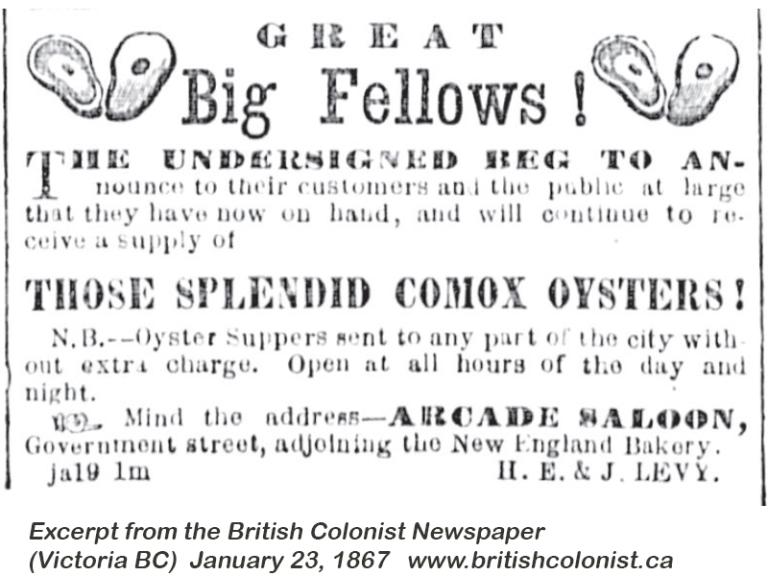

And following this obvious manipulation of the press room, the ad that appears the following week on January 23 spells the destination of the Comox oyster harvests onto the menus of the Arcade Saloon operated by the brothers Levy.

Henry Levy opened the Arcade Oyster Saloon in 1864 but soon his brother Joe joined him in Victoria and they expanded the enterprise into a restaurant which became known simply as Levys’.[12] It was a unique establishment with sawdust covering the floor and a parrot and cockatoo for added colour, while offering world class cuisine using imported products from around the world, like turtle from Tahiti and Malpeque oysters from the east coast. Levys’ was in business for 49 years as a leading restaurant in Victoria but its humble beginnings as an oyster bar were reputed to have been commemorated with a large oyster shell on each piece of crockery with the Levy name emblazoned upon it. (oh we would so love to find an example of this crockery)

Fisheries management does not appear to come into play until after Canadian Confederation The colony of British Columbia, which formed from the union in 1866 of the colonies of Vancouver Island and mainland British Columbia, partly due to debts incurred during the gold rush years, only proceeded to enter Confederation in 1871. The Fifth Annual Report of the Department of Marine and Fisheries for 1872 included several promising reports about oysters in its statement of fishery resources in the new province, from which the following excerpts have been taken.[13]

Beginning with the prize winning essay in a government sponsored contest that also notes the presence of larger supplies of oysters from Comox, written by Alexander C. Anderson who would go on to become Inspector for Fisheries of British Columbia.

“Oysters are very abundant. Those dredged near Victoria are of small size, but well flavored; northward, in the vicinity of Comox, a larger sample is procured.” (p. 185)

An official report authored by the Honorable H. L. Langevin, Minister of Public Works includes some enthusiastic predictions for the fisheries of British Columbia in general and for oysters in particular.

“The fisheries of Columbia are probably the richest in the world, but they have been but very little worked. The gold fever draws immigrants towards the auriferous tracts, causing them to neglect what to many of them would prove to be a much richer mine, one yielding much more certain results…..”(p. 179)

“Oysters – Are found in all parts of the Province. Though small in their native beds, they are finely flavored and of good quality. When, in the course of time, regular beds are formed, and their proper culture is commenced, a large export will no doubt take place both in a fresh and canned state. There is a large consumption of oysters in cans on the Pacific coast.”

The following year the Agent of the Department of Fisheries, James Cooper, made the following suggestions from Victoria regarding the benefits of bringing fishery laws to the oyster industry in the Province particularly by granting rights to individuals interested in oyster culture, a few of whom have expressed interest.[14]

“You will ere this have received a communication on I had the honor of forwarding from Mr. Brackman, received through messrs. Janion and Rhodes of this place, relating to oyster culture, &c. I have also received during the past season two similar verba applications from different localities in the Province.

I would respectfully beg leave to offer a suggestion in reference to the fisher laws for the information of the Hon. the Minister of Marine, which in my opinion would meet the present requirements of the province. First, premising that the extension of the fishery laws of the Dominion in their entirety to this country would be productive of not substantial benefit, but would rather probably lead to complications with the Aborigines.

It is, however, desirable that a protective measure should be enacted and extended to British Columbia in favour of such persons that are desirous of embarking in the business of oyster culture, granting certain privileges for a term of years at a nominal rent. There can be no possible objection to such an enactment.” (Appendices p. 205)

Oyster culture in the Province would soon become an important branch of industry if the rights of individuals were secured to them. “

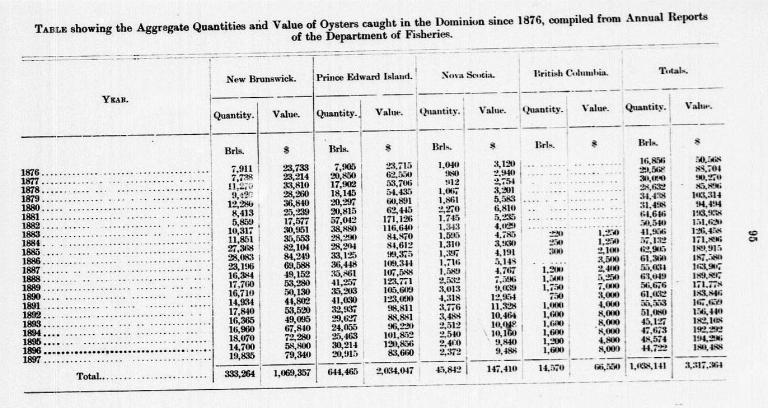

An 1876 Order-in-Council proclaimed that the Fisheries Act of Canada extended to British Columbia. However, the first statistical records for oyster harvests don’t appear until 1884, eight years later, with an account of 220 Barrels (1 barrel contained 250 lbs of oysters) with a value of $1250.[15] The round numbers however make the catch data rather suspect.

As early as 1882, the Inspector for Fisheries for BC, Alex C. Anderson, advises the Commissioner for Fisheries for Canada of the advancements of what was probably the first oyster lease on the coast of BC, and about the potential for two more leases. The Mud Bay mentioned here lay on the south shore of Victoria West but became a garbage dump in 1965 and was subsequently filled in.[16]

“A glance at the table of returns will suffice to show that a considerable increase in the varied sources of yield is gradually proceeding. The oyster business, so far, has made little apparent advance; but the leases of the Mud Bay flats, with recently increased capital, are, I am assured, prosecuting the object of their lease with vigour. Another application for the lease of a portion of Sooke Harbour has been forwarded to Ottawa for your approval; and a third application for the lease of a portion of Victoria Arm also for oyster culture has recently been prepared, and after enquiry, will be forwarded for your consideration.“[17] (p. 189)

The following year Anderson reports collecting $50 from oyster fishery privileges and the issuance of just 2 oyster fishery leases.

“The business of oyster culture, still in embryo, promises favourably. Mr. A. J. McLellan, formerly of Prince Edward Island, to whom a lease of certain tidal waters in the neighbourhood of Victoria was last year granted, has gone energetically into the business. He has imported and planted out several car-loads of oysters from Boston, and there is every ground to hope that his enterprise, so far successful, will be permanently profitable. The Mud Bay Oyster Company, who had previously obtained a lease, have also, as they inform me, taken measures for planting their tract with imported stock; and I anticipate that, with the success of these operations, a lively impetus will be given to the prosecution of the oyster industry in divers favourable positions around.” [18] (Supplement p. 196)

By 1887, the Fisheries Inspector for BC, Thomas Mowat, was reporting the poor state of the oyster industry

“Our oysters are of small size, and only taken in sufficient quantities to meet local demand. Owing to this, a great deal of those used to supply home consumption are imported from oyster beds in Olympia. These oysters are considered of better quality and finer flavour than our own, which is attributed to cultivation and care. Sometimes a few of the transplanted eastern oysters are imported from San Francisco. They are of good size and look healthy, but are not deemed as good as those taken fresh from the Atlantic. We have a number of defined beds on this coast, but for want of proper care and attention they have deteriorated and are now almost worthless.” [19] (p. 250)

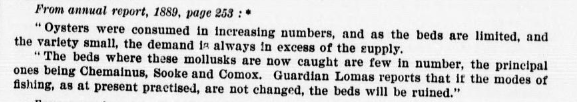

In a report published in 1899[20], a reference to a previous 1889 report in which Comox is mentioned again and the observation that overfishing is already happening.

Cowichan Indian Agent and Fisheries Guardian A.H. Lomas in the 1889 report calls for seasonal closures on oyster harvesting and suggests that private oyster culture should be encouraged[21].

At the same time, much attention is being made to the declining oyster resources of the eastern provinces of Canada with many regulations suggested and imposed to limit overfishing and destruction of the oyster beds, to implement harvest size limits and closed seasons, and encouraging privatization of the resource through designation of leases. The efforts of both the Fisheries Commissioner, Professor E. E. Prince, and an “oyster expert” in the employ if the government, Mr. Ernest Kemp from Whitstable, England, were confined to the east coast except for attempts to transplant lobsters and Atlantic oysters into BC waters in 1896[22] and 1905[23].

With remarkable forethought, the fisheries inspectors for BC from 1907 until 1911, included in their annual statistical report not only the total quantity of oysters caught and landed in a “green state”, but they also divided up the catch data into each of the nine sub-districts within the fishery district of Vancouver Island namely, Nanaimo, Cowichan, Victoria, Clayoquot, Alberni, Alert Bay, Quathiaska, Comox, and the adjacent Mainland (not including the Fraser River delta area). This allows a clearer picture of where the oysters were coming from, which areas produced the most and which showed the greatest decrease and probably depletion during the time period. Oyster landings from Comox for each of the four years 1907-1911 was 160, 140, 150, 80 sacks, respectively for a total of 530 sacks of oysters worth $2120[24]. Since one sack was estimated to weigh 125 pounds that means a total of 66,250 lbs of these relatively small oysters were harvested in those years, or 16,562 lbs per year. At 3000 to 4000 oysters per sack that means approximately 464,000 for half million oysters were harvested each year from the beaches of the Comox area now known as Baynes Sound, probably without much input from “culturing” practices. We can’t assume these were only native oysters since Stafford (1912) noted in his report on the distribution of native oysters in British Columbia that the Dominion government had planted small quantities of Eastern oysters in many places and some of these could have ended up on the shores of Baynes Sound. The records for 1911 only show oyster landings for the districts of Nanaimo and Victoria which could mean that the records were simply consolidated rather than that the other districts were not producing any oysters. However, for the years 1913 and 1914 no oyster landings are shown for any of the districts of Vancouver Island, only from the lower mainland, most probably all from Boundary Bay.

So there we have it…. Native oysters had a significant cultural role in the emerging city of Victoria and an economic one. And Baynes Sound (Comox) supported relatively large beds of oysters that were discovered in 1866 but were in serious decline by 1889 (23 years later). The records showing a harvest of 80 sacks of oysters (10,000 lbs) in the 1910/1911 year must represent the last great effort by harvesters because by the time the first biologist notes only a few small and sparse oysters in a 1913 survey more than 47 years have passed and the beds from memory. Fully a hundred years later we are trying to bring them back.

This seems to be a good example of shifting baselines – without adequate knowledge of the past not understanding fully how the ecosystem may have changed. The oyster story in the newspaper continues – with additions of Eastern and then Japanese oysters – we will deal with this in another blog post.

[2] Stafford, J. 1912. Supplementary observations of the development of the Canadian oyster. The American Naturalist, 46:29-40

[3] Stafford, James. 1915. The Native Oysters of British Columbia. In Province of BC Report of the Commissioner of Fisheries for the Year ending December 31st, 1914 with Appendices. (p. 110-119) Victoria, B.C. 133 pp.

[4] Elsey, C.R. 1933. Oysters in British Columbia. Bulletin 34 of the Biological Board of Canada. Ottawa. 34 pp.

[5] Stanton, L. M., Norgard, T. C. MacConnachie, S .E. M, and G. E. Gillespie. 2011. Field verification of historic records of Olympia oysters (Ostrea lurida Carpenter, 1864) in British Columbia- 2009. Can. Tech. Rep. or Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 2940: vi + 115 pp.

[9] Forbes, Charles. 1962. Prize Essay: Vancouver Island, Its Resources and Capabilities, as a Colony. The Colonial Government, Victoria.

[10] Link to article

[12] Castle, Goeffry. 1984. Henry Emannuel Levi. The Scribe. 18:6-7.

[13] Department of Marine and Fisheries. 1873. Fifth Annual Report of the Department of Marine and Fisheries being for the Fiscal Year Ended 30th June, 1872. Ottawa.

[14] Department of Marine Fisheries. 1874. Sixth Annual Report of the Department of Marine and Fisheries being for the Fiscal Year Ended 30th June, 1873. Ottawa.

[15] Kemp, Ernest. 1899. The Fisheries of Canada. A Survey and Practical Guide on Oyster Culture. Government Printing Bureau, Ottawa. 101 pp.

[17] Retrieved 2014-02-01

[18] Department of Marine Fisheries. 1884. Supplement No. 2. To the Sixteenth Annual Report of the Department of Marine and Fisheries being for the Year 1883. Report of the Fisheries of Canada for the year 1883. Ottawa.

[19] Department of Marine Fisheries. 1899. Thirty-First Annual Report of the Department of Marine and Fisheries 1898 Fisheries. Printed by Order of Parliament. Ottawa, S.E. Dawson, Printer to the Queen’s Most Excellent Majesty. pp. 453 + lxx.

[20] Kemp, Ernest. 1899. The Fisheries of Canada. A Survey and Practical Guide on Oyster Culture. Government Printing Bureau, Ottawa. 101 pp.

[21] Sessional Papers of the Parliament of Canada. Volume 8. Third Session of the Sixth Parliament, Session 1889. Page 250, 251, -Ref at:

[22] Department of Marine and Fisheries. 1897. Twenty-Ninth Annual Report of the Department of Marine and Fisheries 1896 Fisheries. Ottawa. xxv + 405 pp + appendices.

[23] Stafford, J. 1912. Supplementary observations of the development of the Canadian oyster. The American Naturalist, 46:29-40.

[24] Department of Marine and Fisheries. 1912. Forty-Fourth Annual Report of the Department of Marine and Fisheries 1910-11 Fisheries. Sessional Paper No. 22. xlix + 426 pp.