by Jimena Chalchi GP (Jimena.Chalchi@viu.ca). February 3, 2023.

In the following paragraphs I present a review about the ‘Two-eyed Seeing Approach (TeSA)’ concept in order to explain how, during the first gathering held by the ‘Naut sa mawt Center for Psychedelic Research’ there was a collective intelligence dynamic inspired by Ken Wilber's Integral Theory that allowed the definition of recommendations to steward and promote a culturally safe, equitable, intercultural collaboration between Indigenous and non-Indigenous researchers.

NCPR's Seed Group was funded, virtually, in November 2022. During the gathering there were 13 people participating in person. There was a conscious effort to have an equal number of participants from Indigenous ways of knowing and from Western background to ensure equity and diversity in the mapping process. In the following pages I present some concepts that were brought to the center of the circle to open the conversation and analysis around ways of sharing knowledge and the ideal epistemological relation type between cultures for the center.

Elders Albert Marshall, and Murdena Marshall, who belong to Mi’kmaq Nation, together with their biologist friend Cheryl Bartlett introduced the concept Etuaptmumk, rooted in Mi’kmaq Knowledge (2008). This term was translated by Elder Albert Marshall as “Two Eyed Seeing”. Etuaptmumk, was originally introduced as a guiding principle, an approach, or stand point, that enables intercultural cooperation and knowledge exchange.

Intercultural collaboration happens when a person, team, or organization from one culture communicates and works together with another person, team or organization from a different culture towards a common goal.

During their work and because of their context, Elders Marshall and Cheryl Bartlett have expressed special interest in the collaboration between Indigenous and non-Indigenous ways of knowing. “Two-Eyed Seeing can help us understand how our traditional teachings, our Traditional Knowledges, can work together with the knowledge of the newcomers for a better and more healthy world” (Bartlett , C., et al. 2018. p. 45).

In his recent work through the Integrative Science Institute, Elder Albert Marshall explains that Etuaptmumk can also be used as a guiding principle for collaboration between two, or more cultures: “one might wish to talk about Four-Eyed Seeing, or Ten-Eyed Seeing, or 3265-Eyed Seeing, etc”. It is also important to remark that, as A. Marshall actually presents it, the principle of Etuaptmumk is not exclusive for Indigenous and non Indigenous collaboration, but it can involve collaboration between two or more different non-Indigenous cultures, or different Indigenous cultures. The highlight is that Etuaptmumk is a principle that belongs to the Mi’kmaq culture and describes the willingness of someone to participate in what the Western worldview understands as intercultural collaboration for the common wellbeing.

Lee-Anne Broadhead and Sean Howard (2021) explain that since its introduction in 2008, the TeSA has become common in academic research. However, it has been employed “almost exclusively in areas with comparatively bridgeable divides: ecology and environmental science, health and medicine, psychological disorders and therapies'' (p. 113). This, the authors explain, is because other areas of research such as policy making, educational programs, research methodologies, and others are more controversial when confronting Indigenous and Western worldviews.

Despite the scholarly ‘conflict-avoidance’ in these research areas, there are many discrepancies when interpreting and applying the TeSA: “some suggest that Two-Eyed Seeing encourages the bridging of Indigenous and Western knowledge, while others see Two-Eyed Seeing as encouraging the blending or integration of Indigenous and Western knowledge”. (Roher, S., et al., 2021, p. 2). Furthermore, some researchers consider that both ways of knowing can converge to create new concepts in a “transcendent, trans-cultural third space” (Broadhead, L.A., p. 114). Because of these different ways of sharing knowledge, it is fundamental to consciously choose the ideal epistemological relation type that will be established between stakeholders when thinking about TeSA.

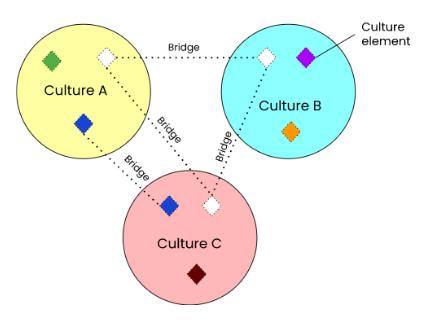

When we speak about bridging Indigenous and Western knowledge we come to delicate quicksand because western culture is absolutely dominant, expansive and hegemonic. However, the idea of bridging knowledge means that there is a cross-cultural relation, where the partnering team tries to find the differences and similarities between cultures, and find the concepts that naturally bridge and co-relate (Reid et al. 2006). “We define bridging knowledge systems as maintaining the integrity of each knowledge system while creating settings for two-way exchange of understanding for mutual learning” (Rathwell, K. J., 2015, p. 853). See figure 1 for a graphic description of this kind of relation.

Figure 1.

Cultural bridging.

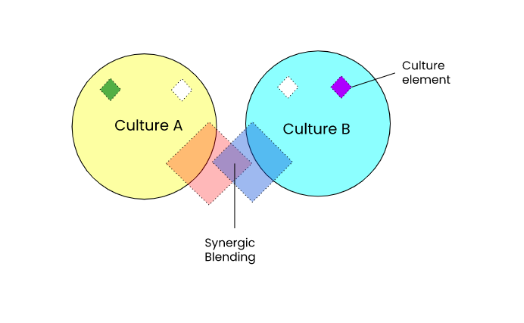

On the other hand, when speaking about blending or braiding knowledge the team will try to connect concepts and relate them synergically, unifying them towards a specific goal in an integrated manner without losing track of their origin. (McCormack, B., 2006, pp. 257-258). An example for this kind of relation is the use of Indigenous traditional medicine plants in Western naturopathic practice. See figure 2 for a graphic representation of this relation.

Figure 2.

Cultural blending.

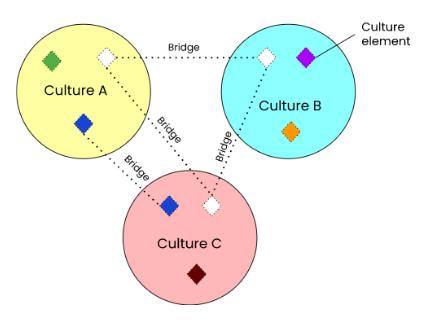

Alternatively, there is another way of dialogue “in which two scientific traditions create a transcendent, trans-cultural third space” (Lee-Anne Broadhead p. 114). The objective is to reflect on ideas and concepts, in order to come to agreements that allow a safe, equitable space for each one of the cultures to express and participate in the endeavor. This third space starts by creating momentum for understanding each culture's perspectives and the relation that will be built between them and that will be held towards knowledge. The result of this is a completely new experience of understanding and learning that permeates the whole. Please refer to figure 3 for a graphic representation.

Figure 3.

The third space.

Two-Eyed Seeing collaborators seek nothing less ambitious and profound than “a shared vision that can be neither situated within the Western or Indigenous way of knowing but somewhere in the space in-between or fusions of new horizons” (Hovey et al., 2017, pp. 1285–1286). “A third space, a liminal space, in which we build a sharing relationship while maintaining the integrity of each identity and voice” (Bartlett, 2015, p. 25).

Before going further, it is important to highlight that, in order to blend, bridge, or create a third space, researchers have to approach knowledge as an object that can be connected, modified or complemented. TeSA implies that, from a respectful intercultural relationship, this knowledge-object can be taken out of its original paradigm and relation to reality, to be used in certain situations and from a certain perspective. Shawn Wilson (2001) explains that this way of objectifying knowledge belongs to the Western dominant paradigm: “dominant paradigms build on the fundamental belief that knowledge is an individual entity: the researcher is an individual in search of knowledge, knowledge is something that is gained, and therefore, knowledge may be owned by an individual” (p. 177). On the other hand, Wilson explains, Indigenous paradigms hold the belief that knowledge is relational, it happens in relation with all Creation. “It is not the realities in and of themselves that are important, it is the relationship that I share with reality. It is not necessarily the object that is important, it is my relationship with that object that becomes important” (p. 178).

The challenge that researchers face when sharing knowledge when using TeSA is that they are using a methodology that comes from the dominant paradigm (knowledge-object), therefore, the results of such methodology might be following that dominant paradigm's ways and flows. Shawn Wilson proposes to incorporate a relational perspective in research: “Our systems of knowledge are built on the relationships that we have, not just with people or objects, but relationships that we have with the cosmos, with ideas, with concepts, and everything around us” (p. 177).

The Seed Group gathering was formed with the understanding that, in order to overcome challenges and lines of thinking, it is fundamental to come to an agreement and understanding of the relationship type that the research team will hold towards knowledge.

In the specific case of the “Naut sa mawt Center for Psychedelic Research” the decision by common agreement is to have a diverse team that consists in researchers coming from diverse Indigenous cultures, others that come from the dominant Western worldview, and other group from multicultural non-dominant, non-Indigenous origins. Because of these, and considering what Elder Marshall explains about the many eyes that can be included in the Etuaptmumk concept, for the Nawt’sa mawt Center’s Seed Group it is important to step out of the translation ‘Two-eyed seeing approach’ and move towards ‘Intercultural Third Space’, even when the team has decided to keep working with the Etuaptmumk concept.

Another recommendation is to define methodologies that will shape the framework by observing the balance between Indigenous and non-Indigenous paradigms. Because of colonization, the biggest effort has to be invested in understanding and integrating Indigenous methodologies and paradigms: “In order to appreciate and ‘come to know’ in the Native American science way, one has to understand the culture/worldview/paradigm of Native American people” (Little Bear, 2000, p. x).

Reflecting on these epistemological aspects has been the first step to define the epistemological relation type that will guide the team towards “Naut sa mawt: working together, as one mind and spirit”.

References

Bartlett, C., Marshall, M., Marshall, A., and Iwama, M. (2015). Integrative Science and Two-Eyed Seeing: Enriching the Discussion Framework for Healthy Communities. In Ecosystems, Society and Health: Pathways through Diversity, Convergence and Integration. MQup. pp. 280-326.

Bartlett, C., Marshall, A., & Marshall, M. (2018). Two-eyed seeing in medicine.

In Determinants of Indigenous peoples’ health in Canada: Beyond the social. Canadian Scholars' Press Inc. pp. 16-24.

Broadhead, L., Howard, S. (2021). Confronting the contradictions between Western and Indigenous science: a critical perspective on Two-Eyed Seeing. AlerNative: An international Journal for Indigenous People, 17(1) pp. 111–119.

Little Bear, L.. (2000). Forward. In G. Cajete, Native science: Natural laws of interdependence (pp. ix–xii). Clear Light Publishers.

Marshal, A. (2017, September 28). Two-Eyed Seeing – Guiding principle for inter-cultural collaboration. [Speech audio recording].

McCormack, B., Titchen, A. (2006). Critical creativity: melding, exploding, blending.

Educational Action Research, 14(2). pp. 239-266.

10.1080/09650790600718118

Rathwell, K. J., Armitage, D., & Berkes, F. (2015). Bridging knowledge systems to enhance governance of environmental commons: A typology of settings. International Journal of the Commons, 9(2). pp. 851–880.

Benoit, A., Martin, D., Sig, R., & Yu, Z. (2021) How is Etuaptmumk/Two-Eyed Seeing characterized in Indigenous health research? A scoping review. PLoS ONE 16(7): e0254612.

Wilber, K. (2001). A Theory of Everything: An Integral Vision for Business, Politics, Science and Spirituality. United States: Shambhala. 2001.

Wilson, S. (2001). What is an Indigenous Research Methodology? Panel Presentation: Coming to an Understanding. Canadian Journal of Native Education 25(2). pp. 175-179.

This article is the result of a Participatory Action Inquiry processes held for the development of an Intercultural Collaboration Stewardship Plan for the NCPR. Its creation has been possible thanks to the support of diverse communities, individuals and stakeholders with the aim of building capacity for Intercultural collaborative research at the NCPR. The results of this research are the foundation of the Center's Research Framework.

Collaborators

Organizations involved

- Snuneymuxw First Nation Healing Center

- British Columbia Network Environment for Indigenous Health Research (BC NEIHR).

- Roots to Thrive

- Vancouver Island University / Psychedelic Assisted Therapy Graduate Certificate

Seed Group Scholars and Knowledge Keepers

Elder Geraldine Manson, Gail Peekeekoot, Shannon Dames, Jess Shannon, Krys Sciberras, Gordon O'connor, Charsanaa Johny, Vivian Tsang, Robert Nye, Georgina Martin, Emmy Manson, Jimena Chalchi Garcia-Paniagua (facilitator)

Next Stage

Space to clarify the intent: Seed Group gathering.